Many predict irreversible changes in the way we work in the post-COVID-19 world. Examples include less in-person contacts, more use of virtual technology, and thus possibly decreasing levels of global mobility.

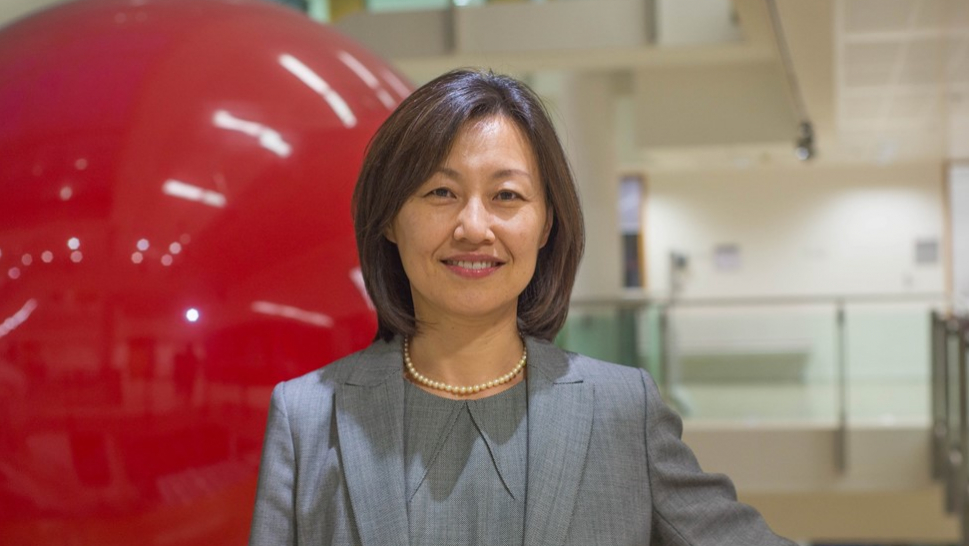

All of this was happening to me and my workplace in October 2020. I rarely interact with my students and colleagues face-to-face these days; I have shopped and explored several new IT gadgets to assist countless virtual meetings; quite a number of new students are yet to arrive in London even though the LSE’s academic year had started one month ago. As a psychologist who specialises teaching and researching cross-cultural management, I share my observations of what appears critical for teams to succeed in a multicultural virtual space.

Misunderstandings in multicultural teams

Multicultural teams are prone to misunderstandings due to cultural differences in their communicative norms and conventions. This is especially the case between members who hold different tastes in the desirability of critical feedback and direct communication. Critical feedback is an opportunity to develop and improve for some, but for others it can be seen as an invitation to fight. Similarly, whereas direct communication can be an efficient way of expressing inner thoughts for some, it is considered impolite for others. These tastes are largely shaped by the culture, and deeply embedded in psyche. If individuals of opposing communicative taste work together, misinterpretations of the other’s motives can develop into emotional frictions. Going virtual adds further complications, because virtual interaction removes many useful non-verbal cues which help ease frictions.

What makes a successful team in the time of Covid-19

The COVID-19 lockdown of London in March 2020 provided me with a rare opportunity to closely observe how such misinterpretations can get out of control in multicultural and multilingual student project teams, who had to work virtually. Student project teams at LSE had to switch their working mode to 100% virtual, almost overnight and without preparation. When the project was all over and we all had a moment to reflect on the team process, one common theme emerged: emotional frictions in teams.

Almost all teams experienced emotional frictions resulting from different, often contrasting communicative habits between members, but some teams were able to overcome these challenges and even flourish.

“Successful” teams tended to address these emotional frictions openly by recognising and talking about them. Importantly, successful teams often noted a member or two who first sensed the hurt feelings of others, then acted to broker across members. These brokers were frequently perceived as leaders in the team.

The importance of emotional intelligence

The key takeaway point from these observations is highly relevant to the leadership skills we seek for in the post-COVID-19 world. The seemingly natural ability to detect when something is misinterpreted by different cultural members (cultural intelligence) and to sense the hurt feelings of others (emotional intelligence) will become increasingly important skills to operate in virtual and multicultural environment. They will no doubt be highly sought-after qualities in post-COVID-19 leadership.

For more insights from the CEMS Global Alliance on Leadership in a Post Covid-19 World, visit: https://cems.org/news-events/media-centre/press-center